‘Poets and pornographers’ and other poems

by Alex Leigh Farber

The poets and the pornographers

meet in the same place

every night—

after the city has emptied out.

Neither tourists nor police

can tell them apart.

‘If the Queen Shows up in a Double Rainbow’ and ‘Teardrop Pearls’

by Mitzi Dorton

Signs

After death,

Wouldn’t they come

From a mother, too,

Who bangs on the glass

At the emergency room,

The desk ladies talking,

Lost in their own family sagas

War Cake

by Charlotte M. Porter

Enduring bloodshed, recipes, women’s spoils,

make do w/ shortages, rations & absence

of manna, milk & honey, miracle loaves—

foody promises made real in War Cake,

a city confection for cooks w/out chickens,

an eggless feat, almost fat-free w/ raisins,

minus milk, to fete a special occasion

as soldiers die on someone else’s T.V.

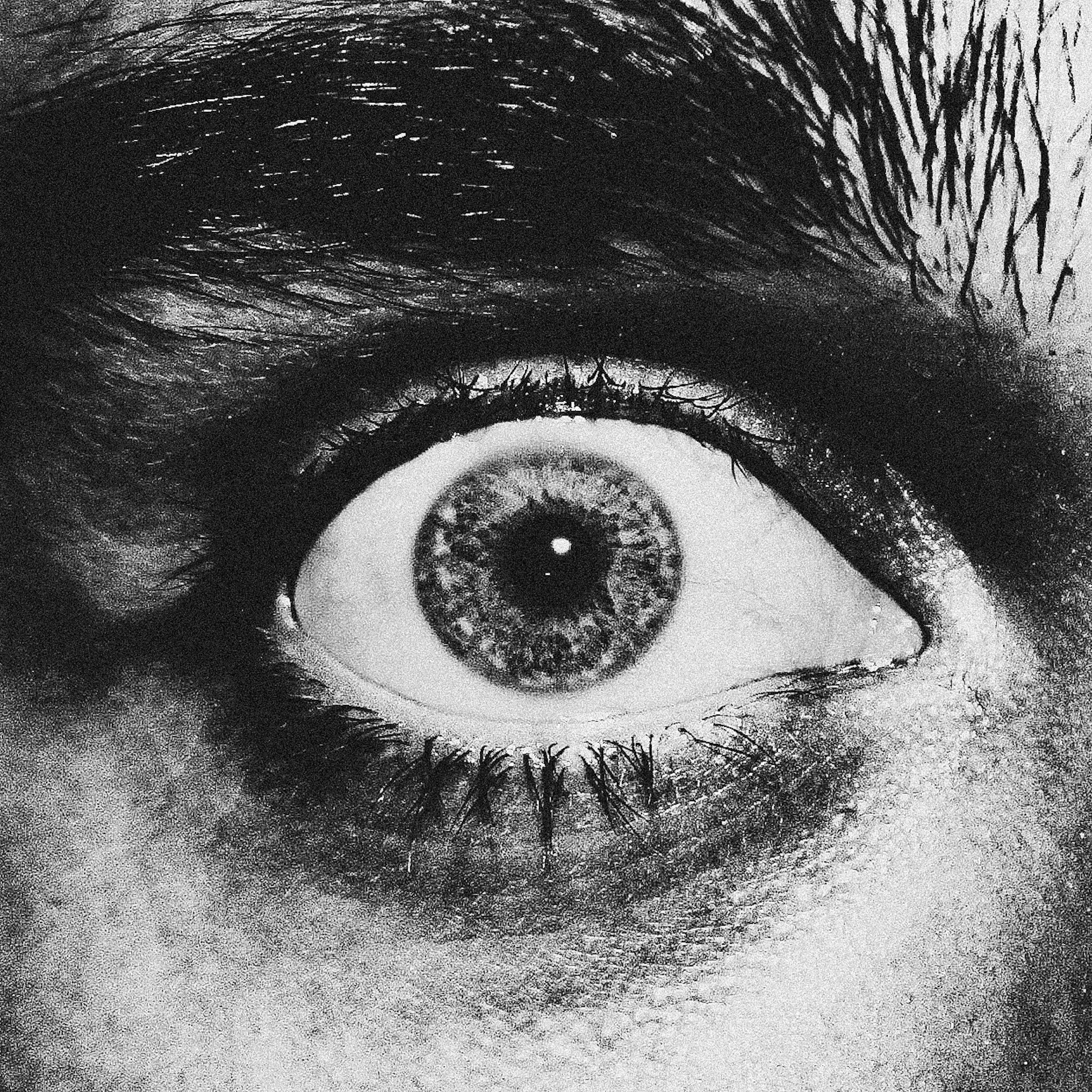

What Tricks the Mind

by Rita Taryan

The comeliest woman in the village is the one with the roundest face and rosiest lips. The most eligible bachelor in the village is the one who writes the most heartfelt poetry about his mother. The great Hungarian poet, Attila József (working-class, schizophrenic, a suicide at the age of thirty-two) wrote, “For a week now, all I think about is Mama; When I stop, I start again.”

‘A word fallen out of language’ and other poems

by Milena Findeis

In the mouth, the word

to taste

to chew

It hums in the ears

is rolled by the eyes

cut apart by grimaces

Spread with hashtags

processed in the news stream

until it ends, checked off,

in the cache

What will people say?

by Mire Marke

She tells me not to sit on the cold stone slab in front of the fireplace. It will ruin your womb, she says. You need your womb. I tell her I don’t want children anyway. Flames burst from her mouth in the shape of what will people say?

‘The Mother’ and other poems

by Ema Dumitriu

In fleeing me, my wrath,

my fear

a female rat is giving birth

on the hot sidewalk,

steadily,

trailing behind a streak of blood

with child

The Ones Who Survive Are Real — a Review of Bora Chung’s ‘Red Sword’

Reviewed by Kate Tsurkan

Bora Chung’s “Red Sword” wastes no time plunging readers into an alien world that is both cruel and enticing, immediately challenging humanity to find a way to reclaim itself. We are first introduced to the narrator — a woman who remains nameless for most of the novel — as she recounts her budding intimacy with a lover aboard a slave ship traversing the far reaches of a galactic empire, only to witness his death shortly after they are cast onto what is dubbed the white planet. What starts as a flicker of dread from her lover’s untimely death swiftly grows into an unrelenting tension that saturates the novel from start to finish.

When the Air Held Its Breath — on the Poetic Record of War in Oksana Maksymchuk’s ‘Still City’

Reviewed by Anya Avrutsky

Written in the few months leading up to and following Russia’s full-scale invasion, the book bridges a documentary and surrealist style, capturing a city on the brink. Maksymchuk, a Ukrainian poet and translator from Lviv, began writing Still City six months before February 24th, from a building overlooking an old prison courtyard where political prisoners had been executed during WWII. Such a setting serves as a reminder of how little time has passed since the last war that ravaged Ukraine.

‘In the passing’ and other poems

by Alexandra Magearu

a tumult of birds

like a little chaos

thick and fluttering

with treasures in their toothless mouths

cruel in the glacial light

(…)

Two wartime poems

by Olena Herasymiuk

Translated from the Ukrainian by Viktoria Ivanenk

I am standing on the stage that

no longer exists

it’s not a stage — it’s a mass grave,

under it

buried alive, lie thousands of

men, women, and their children —

the dead, the living, and the unborn

An excerpt from the novel ‘Swan Song’

by Miklós Vámos

Translated from the Hungarian by Ági Bori

As an officer of the armed forces, he made certain to stare the defiant privates in the eye until the last moment. However, he couldn’t stop the wrinkles from forming on his forehead.

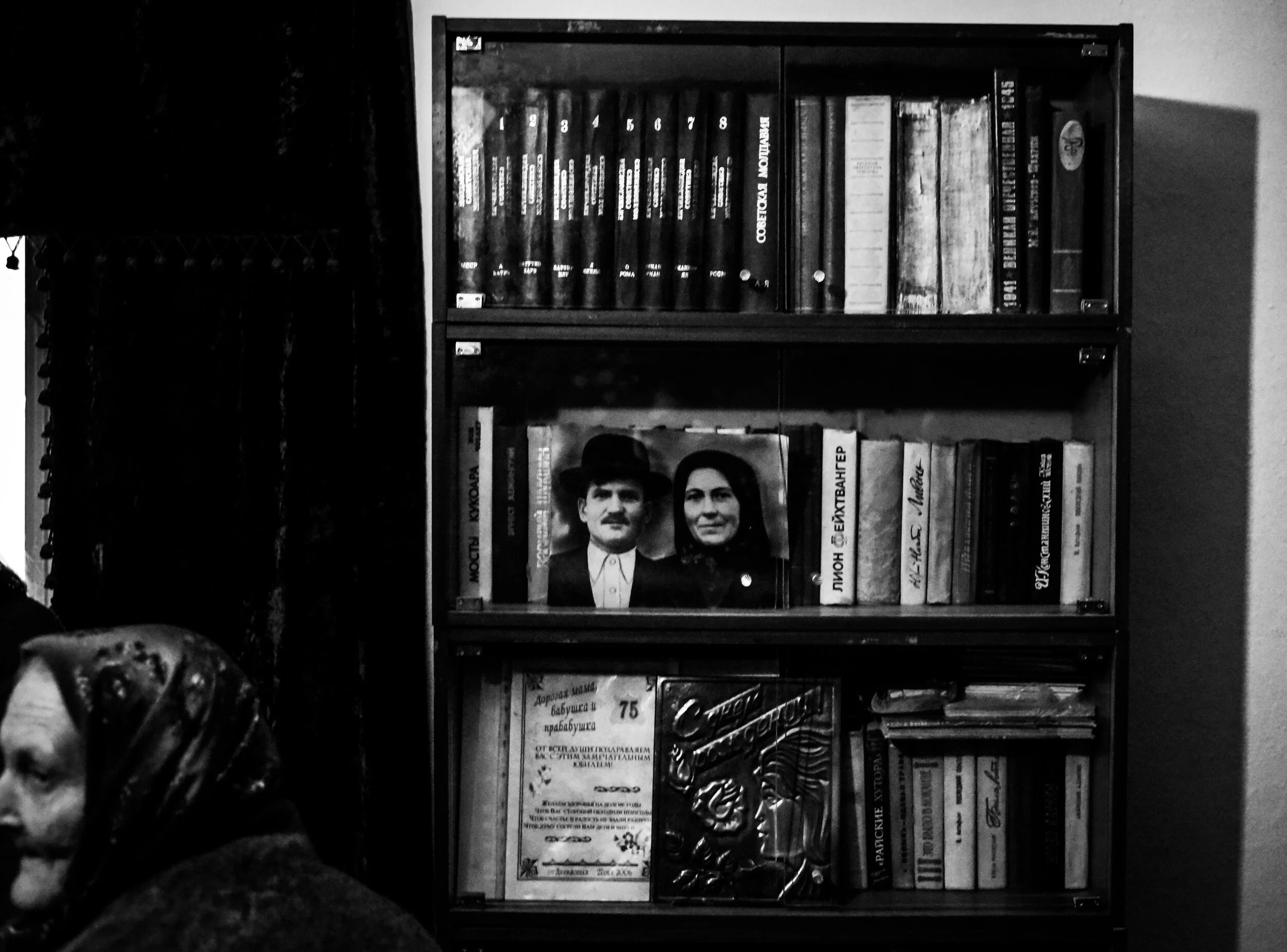

A Room without Shadows

by Andriy Sodomora

Translated from the Ukrainian by Sabrina Jaszi and Roman Ivashkiv

There before me was a bare window without even the sheerest covering, and in an instant I took in the whole room: It was lit by a bright incandescent bulb dangling from the ceiling on a long wire. In the middle of the room, on a little stool directly under that light, sat an old woman, wrapped in some dark garment, her head covered by a dark kerchief.

Night Shift

An excerpt from the novel Vanilla Ice Cream by Đurđa Knežević

Translated from the Croatian by Ena Selimović

After nearly two consecutive shifts—afternoon into early morning—her body teetered between numbness and pain. Or rather, when at rest, it grew numb, and when she’d had to move, the pain would flare through her whole body, not just in its moved part.

Reading ‘The Eyes of Gaza’ From Wartime Ukraine

Reviewed by Kate Tsurkan

Reading “The Eyes of Gaza” from Ukraine, I was reminded of how no war occurs in a vacuum — the fight for survival, freedom, and justice is never isolated, but part of a larger human story.

Irena Karpa: “If fear arises, I always go and do what causes it”

Interviewed by Olena Lysenko

“I’ve never had any taboos when it comes to humor. However, I would never joke about the victims of violence, and I do not support sexism or victim-blaming. That’s unacceptable for me. Humor always remains somewhat incorrect and absurd.”

Confronting the silence: An Interview with Monica Cure

Interviewed by Irina Costache

"For me, being able to read these stories fills in a lot of gaps. Many times, it's not because anyone in my family or the Romanians that I grew up with in Detroit are withholding that information, but something that particularly writers can do is make a whole world come alive, a whole time period come alive."

“We Migrating Birds”: Translating the Poetry of North Korean Defector, Imu Baek

Interviewed by Sandra Joy Russell

“Many of the circumstances Baek depicts in her works are dire. In addition to the hunger, cold, and violence the narrator describes, there is a general feeling of helplessness which echoes throughout the work. This made it difficult to continue to translate for extended translation sessions.”

Between Nostalgia and Uncertainty: A Review of Libuše Moníková’s Transfigured Night (2023, Karolinum Press)

Reviewed by Anna West

Libuše Moníková’s Transfigured Night (2023, Karolinum Press) was published in German in 1996 under the title Verklärte Nacht and was only recently translated from German into English by Anne Posten. It is the last completed novel by a writer of Czech origin who nevertheless identified herself as a German author.

Soňa and children

by Richard Pupala

Translated from Slovak by Julia and Peter Sherwood

The faces around Soňa, the curious ones as well as those who were shocked, gradually turned expressionless as if something had switched them off, all but one that remained unforgivingly distinct. She had to flee from Peter’s gaze into the only arms that remained for her.