“I Saw the Other Side of the Sun with You”: Female Surrealists from Eastern Europe

by Juliette Bretan

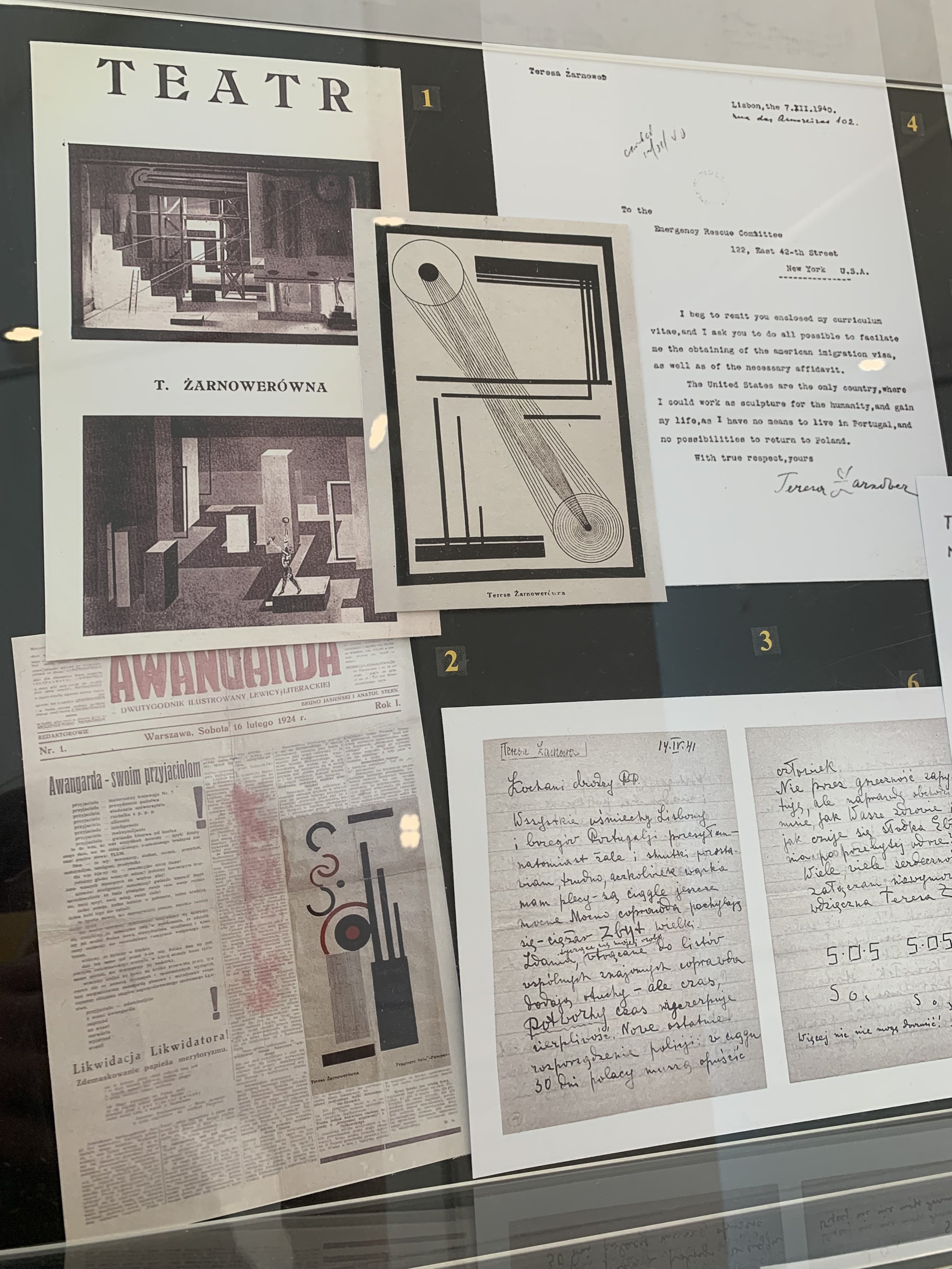

I’m looking at a letter written over 80 years ago, in tidy cursive, which has been placed among copies of journals, diagrams, photographs, and pamphlets on a black table at the center of the ‘Female Surrealists from Eastern Europe’ exhibition at Cromwell Place in London.

It begins quite conventionally – the first line describes the “smiles of Lisbon and Portugal’s shores” – and it really wouldn’t have caught my attention, were it not for the appallingly bleak letters marked out in almost mechanical style, boxy and striking, on the second page:

S.O.S S.O.S

And again, below, but this time scrawled and drifting down the paper:

Sos

Sos And, finally, a short note, in tiny writing: ‘There is nothing else to add – sos!’

The author of these words, written during wartime terror in April 1941, was the Polish-Jewish avant-garde artist Teresa Żarnower – a figure little known in the West, despite her brilliance and prominence in Polish interwar artistic circles – and she was pleading for help to escape the insecurities of exile in Portugal, and flee to America. Żarnower had sent this missive to the Polish author Józef Wittlin and his wife Halina, who were already in the States, with the hope that they could use their artistic contacts to speed up her visa application. Several other letters and documents about her case are also included in the exhibition, testifying to her increased desperation. There is one letter to the Emergency Rescue Committee, a team based in New York to support European refugees, which extols America in faltering English as ‘the only country where I could work as sculpture for humanity, and gain my life’, including her CV as evidence.

Eventually, Żarnower did reach America, but the inclusion of these documents in the middle of the exhibition floor serves as a reminder of the complex networks of wartime efforts to save individuals from persecution in Europe.

They are also documents which, just as vitally, serve a reminder that many of the Surrealist paintings, sculptures, and photographs in marvelous penumbra around them are more than melting clock motifs or subconscious-fuelled experiments of an aesthetic automatism, and rather potent expressions of the trauma of twentieth-century East Europe.

Curated by art historian and critic Anke Kempkes, and commissioned and presented by the European ArtEast Foundation, “I Saw the Other Side of the Sun with You’”: Female Surrealists from Eastern Europe was the world’s first exclusive showing of female Surrealist art from the region, with several of the featured artists exhibited for the first time in the U.K. It followed the development and contestation of Surrealism in Eastern Europe from the 1930s to the present, emphasizing their local variations and complex lineages, as well as illuminating the work of individuals still shamefully overlooked in Britain, but who were adept across disciplines: producing paintings, and sculptures, writing, photomontages, architecture; working as editors and exhibition organizers; and often also producing politically-engaged material. Featured art included those by artists from former Czechoslovakia – which had perhaps the most programmatic approach to Surrealism in East Europe, with its close ties to Parisian proponents, and glittering exhibitions (in 1932, Prague’s river-straddling Mánes Exhibition Hall hosted what was then the largest exhibition of international Surrealism). There was also a notable collection of works from Poland from the mid-1940s to the contemporary art scene, despite the lack of any consistent or committed Surrealist movement in the country. Though several Polish artists demonstrated Surrealist tendencies, in many cases, it was critiqued or supplanted by other movements, particularly Constructivism, which enjoyed far greater popularity. The exhibition also included works from the former Yugoslavia, including those by artists associated with the late Surrealist and retro-modernist Serbian Mediala group, and more recent pieces from Ukrainian artists responding to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

There was something about placing these artworks together in Cromwell Place – one of those ubiquitous wedding-cake-style townhouses of high Kensington, all whitewashed walls, floor-to-ceiling windows, and clean spotlighting – that made this exhibition, somehow, even stranger; as if each artwork fractures something of reality, or allows a glimpse into another form of it. The show spans two rooms, split by a central wall and a couple of parallel doorways (the black plastic frames around them made me think, at first, that they were just mirrors), and even at first glance, there are suggestions of peculiarity.

Two ghostly-white plaster hands curl out from the wall, pockmarked with a trypophobic slash of black bullet holes; next to them, a ribcage splays, bare and fossil-like, across a calloused surface. Both are artworks ("Ruce," or "Hands," 1968; and "Unnamed: Hrudn!k," or "Chest," 1979) by Czech artist Eva Kmentová, whose sculptures often feature broken body forms, stripped and solidified to near rigor-mortis in brute cement or plaster; "Ruce" was created in 1968, the year of the Prague Spring, a brief period of liberalization in former Czechoslovakia. Down the room, a canvas shows two bones in parallel on a desert landscape, beneath a dusking sky; one with a pin in its center as if specialized in the wild. This is the 1952 work "Preji vám mnoho zdraví!" ("I wish you good health!"), by Czech painter Toyen – who adopted that name as a gender-neutral pseudonym in 1923, worked within the internationally-connected Czech avant-garde Devêtsil group, and became a central figure in Czech Surrealism through a vast oeuvre of works witty in their combination of dreamlike scenes, transgressive sexuality, eroticism, and morbid humor. Across the exhibition space, on the far wall, a wire tracks up to a glowing, golden bum: the polyester-resin “Buttocks Lamp” (1970) by Polish pop-artist sculptor Alina Szapocznikow, whose sculptures blend the body with everyday objectivity – placing miniature fragments of flesh atop, for example, dessert bowls, or on light fitting – with a cutesy, playful, and sweet-toothed horror hinting at human vulnerability. Then, in the second room, there are montages among the ruins by Polish photographer Zofia Rydet, as well as vixen magic by contemporary Polish artist Agata Słowak, whose paintings feature provocative scenes of fawning and scantily-dressed women-cats, mewling under nets.

By contrast, post-war political repression meets the licentiousness of abstract art in works by Polish-Jewish artist Erna Rosenstein. One, heavy-hued in deep red, is titled “The artist getting defended in Front of a Meeting of the Union of Polish Artists and Designers.” Others are layered into collages and Magic Eye-esque hidden meaning, flecked with keys, photographs, stamps, and paper. Rosenstein’s "Ekrany" ("Screens," 1951), with its two hovering heads, might be familiar from last year’s Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition at Tate Modern. Rosenstein was also a skillful interdisciplinarian, and her wider output also includes structural assemblages, poems, and fairy tales.

Of all the artists featured in the exhibition, Franciszka Themerson is likely to be the best known. The avant-garde, anti-fascist, collage film Europa – which she produced with her husband and often co-creator Stefan, and which was based on a 1925 futurist poem by Polish artist Anatol Stern – was rediscovered in Germany’s national archives in 2019, after being thought lost for decades. While most of her work with Stefan manifested as high-octane, Dada-fuelled artistic experimentation with innovative approaches to literature, film, and photography, here she is raw and nascent: three of her scrawly 1970s oil compositions feature in the exhibition, which are examples of eerie monochromatic expressionism; setting-less, dynamic, and curious.

All the artworks featured in the show are characterized by similar tendencies towards abstraction, existentialism, and the organic – variously manifested through gestures to pain or indulgent pleasure – which serve as suggestive, trauma-charged allusions to real events. Surrealism became an aesthetic mode to render, process and manage the distressing experiences of twentieth-century history as, through the chaos of war, political repression and brutality, the real world itself became in ways surreal. Artists embraced Surrealism as a sort of grim fantasia, with bodies reduced to the skeletal, and landscapes scorched to black, with horrors suggested but never confirmed. Many artworks also show a particularly feminine dimension to the effects of violence and the possibilities of subversive liberation.

A couple of works in the exhibition are by Żarnower, created only a few years after her desperate letters asking for help to reach America. Żarnower was also an interdisciplinary artist, working on a mixture of sculptures, photomontages, book covers, posters, and architecture, and producing geometric compositions – jarring things, all wavy lines, slashes, and circles – over the course of her ultimately short life (she died at the age of 48 in New York). But her works which feature in the exhibition transform the brute figurations of abstract art into the vulnerable body: one from 1945 shows a female figure, head beyond the canvas, tottering across a blood-speckled landscape of barbed wire, guns, and crosses. It’s scary and troubling, but it is true to the human experience in East Europe during and after the war. Moreover, it showcases a Surrealism which is neither aestheticized experimental practice, nor easy cultural collaboration but rather one which reflects a brutal, horrifying, and isolating reality.

"I Saw the Other Side of the Sun with You": Female Surrealists from Eastern Europe was at Cromwell Place from 12-30 April