“Ukraine has never left me”: An Interview with Dmytro Kyyan

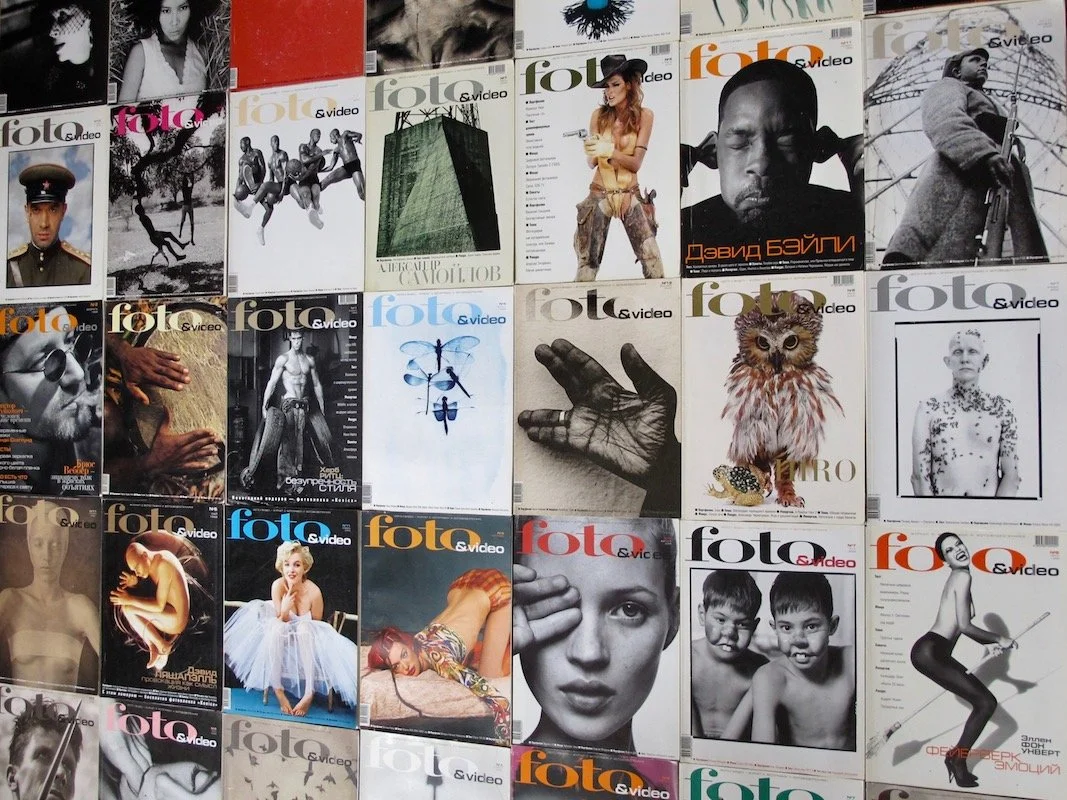

Dmytro Kyyan is a Ukrainian-American writer, editor, and translator from Kharkiv. From the 1990’s to the early aughts he was the editor-in-chief of Foto & Video Magazine and under his direction it became the leading publication in photography not only in Russia but throughout Eastern Europe. Following a criminal takeover of the magazine, Kyyan left Moscow and settled in New York, where he went on to work as a translator and teacher. He has helped to introduce numerous Ukrainian writers to English readers through his translations and interviews. Kyyan spoke to Kate Tsurkan about growing up Ukrainian in the Soviet Union, how the Russian invasion of Ukraine has changed relationships between people from both countries, what makes him proud of Ukraine’s younger generation, and more.

You were born in Kazakhstan, where your parents first met during the Virgin Lands campaign. It was presented to the youth of the USSR as a chance for adventure, and indeed the fact that a Ukrainian man and Russian woman met in Kazakhstan and fell in love has a hint of romanticism to it. However, if one commits to more than just a surface-level reading of Soviet history, they come to understand that things were more complicated than they seemed to the outside eye back then. What was it like growing up Ukrainian in the Soviet Union? How in touch were you able to be with this part of your heritage?

Growing up in Kazakhstan, my father always called me Dmytro, not Dmitry. My birthdays were always announced in Ukrainian: Z dnem narodzhennya. The last day of December was always associated with the Ukrainian words Z novym rokom. However, my real Ukraine entered my life one day in the hot summer of 1980. I was in the Soviet version of a jeep car with my father—speeding up a dusty road through the fields of God knows where in Kazakhstan—when I first heard him sing ‘Chervona Kalyna’. He wasn’t singing the song too loudly, as if it was reserved for himself and no one else: “Oi, u luzi chervona kalyna… pohylylasya… / Chohos’ nasha slavna Ukrayina… zazhurylasya…” So, he was quietly singing that song to himself, with his eyes peering into the distance, just him and no one else around. I had never heard that song before, and my father was somehow a different person at that moment. He was always cheerful and used to crack jokes, but at that very moment in the car, there was no sign of cheerfulness, only a pensive somberness. Many years later, my mother told me that she had always been fascinated by the Ukrainian songs she had heard in Kazakhstan: “There were so many Ukrainians there, and they would always sing their melodic songs every time they had a chance to get together for dinners or birthdays.”

In the summer of 1981, my father went to Ukraine, came back several weeks later and said to my mother, “We are moving home.” I consider his decision a pivotal moment in my life, a strong cultural turn. The symbolic reminder of it is kept in my New York apartment to this day – my very first Ukrainian language book. This is Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar with three short lines inscribed by my father with his favorite black ink fountain-pen on the title page – Kyiv; 05.05.1980; signature.

And, of course, there were all those dinners with my Ukrainian relatives in now-occupied Berdyans’k, the small town of my childhood summers where my grandmother Tanya lived and whom my father would always address using Vy, the formal version of ‘You.’ This is where my Ukrainian heritage literally wrapped itself around me. I would see my Ukrainian relatives, whom I hardly knew and had discovered as being scattered historically around Ukraine—from Zaporizhzhia and Tokmak to Berdyans’k and several villages on the Azov shore. The clippings from our relatives’ pasts, here and there through the years, would start developing into real-life episodes and form a documentary in my mind. Unfortunately, many frames were missing and lost to history. However, I learned that my great-grandfather had sent my then-sixteen-year-old Ukrainian grandmother to possible safety at our relatives’ home in Berdyans’k. And she walked alone through the Ukrainian steppes south of Huliaipole to escape the dangers of the Civil War. When I was thirteen or fourteen, my grandmother also told me that her great-great-grandfather had been a chronicler in one of the Azov Cossacks regiments at the end of the 18th - beginning of 19th centuries.

And on top of all things Ukrainian, there was my grandmother’s sister, the legendary Grandma Hasha. I only vaguely remember that almost fairytale-like Ukrainian lady, as she passed away when I was around six years-old. She is considered somewhat no less than the Great Protector of the Kyyans in the first half of the 20th century, the key-link of all my Ukrainian relatives. She was very close to my grandmother and I know her as someone who was always around for her three sisters and one brother during the times of hardship in the 1930s, the Holodomor, the Nazi occupation of Ukraine in World War II, and the hungry post-war years… And when she saw my mother for the first time in Berdyans’k in early the 1960s, the first thing she did was tell her they should go together and buy some nice summer fabric to make a beautiful dress for her. And so she did.

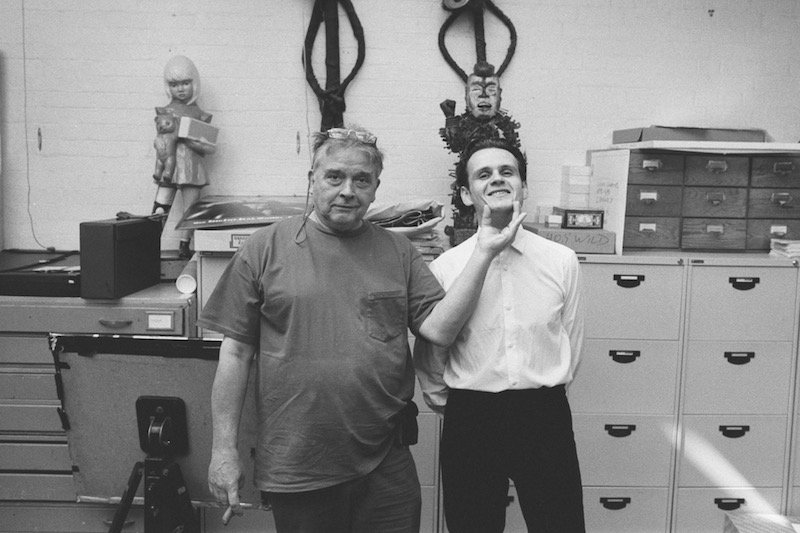

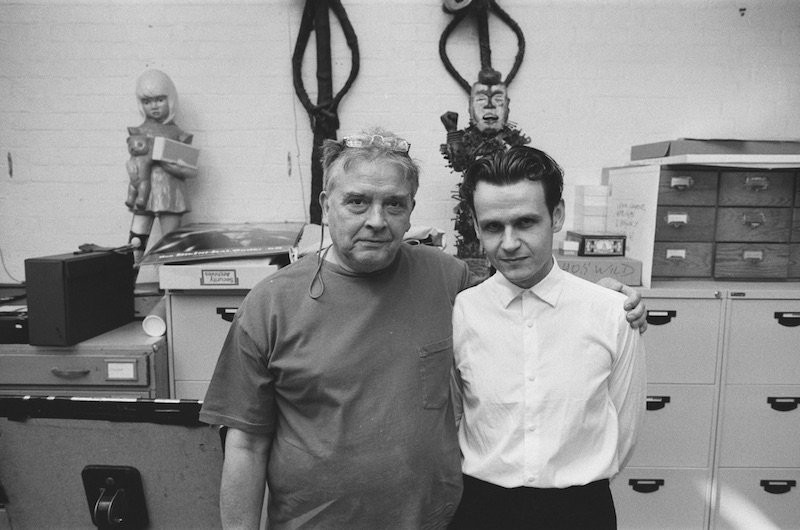

Dmytro Kyyan with the legendary photographer David Bailey in his London Studio, September 1999. Photos from Kyyan’s personal archive.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, you left Kharkiv with $54 in your pocket and went to Moscow, where you founded Foto & Video Magazine. What was it like living in Russia during the 90’s? Did you feel that manic optimism which many have described when referring to their lives during that time, or was the dark path accelerated by Putin always evident?

In the ’90s, Moscow was full of freedoms, a true center of post-Soviet cultural life. Contrary to what Russia turned into today—an international terrorist organization—those years in Moscow were the times one could describe simply with the words’ everything was possible.’ It was the city for young people in their mid-twenties and early thirties looking to make their dreams come true, living in ‘the times of changes’ as we thought back then. It was a city filled with numerous art exhibitions, concerts, and clubs. Those were the times when world-famous magazines were launched on the Russian market, like Vogue and Elle. Many TV shows were broadcasted live, both entertainment and politics, and the print media was independent.

According to Freedom House, Russia was considered a ‘partly free’ country in 1999-2000, the same standing since 1992. Yeltsin named Putin, a former KGB officer who had been a chief of the FSB since July 1998, as prime minister in August of 1999. Then, in December of the same year, he named him his successor. Any thoughtful observer back then could say that Russia’s days as a ‘partly free’ country were numbered. And you didn’t really have to wait long for your fears to come true.

It was already in August 1999 when the second Chechen War started. In September that year, Moscow was shaken by explosions in residential buildings that many believe were FSB-plotted acts to justify the war. In August of 2000, the breaking news which resonated across the world was the Kursk submarine tragedy. While live talk shows continued their coverage for hours in Russia, Putin acted differently. He was silent for a long time, and then, as everyone heard on The Larry King Show, he famously said, “It sank.” He also allegedly called the wives of dead navy sailors, who criticized him for not saving their husbands’ lives, fifty-dollar prostitutes hired to make him look bad. That same year, in December of 2000, Putin decided the Soviet hymn should stay, officially becoming Russia’s hymn. They only slightly changed the lines of the old Stalinist hymn, and even the writer was the same person, Sergei Mikhalkov, an unmatched Soviet conformist who managed to outlive Stalin, Khruschev, Brezhnev, Andropov, Chernenko, Gorbachev, and Yeltsin.

The authoritarian machine targeted the democratic institutions in Russia and began to dismantle them rapidly. Russia’s independent mass media were the first to get under Putin’s attack. It was in April of 2001 when the NTV television company was destroyed. Assassinations of journalists became a routine like news. Artyom Borovik, the chief editor of Sovershenno Sekretno newspaper, was killed in an aircraft explosion in March 2000. Yury Schekochikhin, the deputy chief of Novaya Gazeta, was killed by poisoning in July 2003. The chief editor of Russian Forbes, Paul Khlebnikov, was shot dead in July 2004… Incidentally, I later met Khlebnikov's brother, a history teacher, when I was already in New York.

Freedom House changed the regime status of Putin’s Russia to ‘not free’ in December 2004. That also was my last month and year in Moscow.

The pages of Foto & Video featured not only the work of legendary photographers such as Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and David Bailey but also emerging photographers from across Eastern Europe, many of whose careers you helped to launch. What struck you the most about the work of your contemporaries? Do such impressions remain with you today?

I met photographers who had never had their works published before; some were slightly younger than me, and others were my peers or slightly older. They saw the world in their own unique way and were influenced by living free and unrestrained, that is, without the limitations of Soviet ideology and censorship. Many have stayed true to their artistic principles up until today. Their works are engaging, and their themes have developed. I am still in touch with a lot of those guys on Facebook or Instagram. What matters even more and is of greater value to me, however, are the talented photographers who never betrayed the basic principles of morality and human dignity. When Russia attacked Ukraine in 2014 and launched its full-scale invasion on February 24 of this year, those photographers expressed their position openly and did so without hesitation.

However, some just went off the radar. You cannot expect everyone to act like a hero but what shocked me most was not the fact they disappeared and not even that they didn’t care to write at least a short note to me, knowing that I am from Kharkiv. I was shocked by how they kept rolling on with this false aesthetic that ‘life is beautiful' and filled with romantic photos.

As if nothing happened in Bucha and Irpin and Mariupol didn’t become Ukraine’s Guernica…

As if no Russian missiles hit the train station in Kramatorsk or the shopping mall in Kremenchuk…

As if my hometown, Kharkiv, is not being hit with missiles every day...

It's clear that a magazine like Foto & Video cannot exist in Russia–indeed, even during the height of its run, you were met with the occasional scandal, i.e. for nude content–but can such a magazine exist in today's Ukraine? If so, what would it look like? My impression is that what made Foto & Video unique was, in some ways, inherently tied to this historical moment following the collapse of the USSR.

Yes, such a magazine could and absolutely will exist in today's Ukraine. Today's market is different and, in many ways, more aggressive, considering the fads that Instagram culture and various smartphone apps created. The publishing industry, as we knew it during the second half of the twentieth century, is in many respects a thing of the past. Today's editors have to be even more creative.

I want to make an important point regarding the scandals you mentioned. Foto & Video was sold not only in Russia but also in Ukraine. During my time as editor-in-chief of the magazine, I never received the backlash from Ukrainian readers as I did from those in Russia. For example, a woman once brought a copy of the magazine which featured nude photos into a TV show studio in Moscow and brandished its pages on screen, yelling into the camera, "Look at these photographs! It's an outrage, aren't you ashamed!?"

Foto & Video appeared when the stars aligned – that is, there was a hunger for such publications in Russia back then. The Soviet Union collapsed, its fake ideology discredited itself, and western culture was highly in demand, whether it was music videos on MTV, contemporary art or photography, etc. However, the times they a-changin' as a certain famous singer once noted. And they changed, indeed.

Since the Battle for Kharkiv began, you've kept a close eye on the latest updates from your native city. What has it been like to watch Kharkiv finally shed the title of a "Russian-speaking city" and reclaim its Ukrainian identity as it continues to stand firm against Russian aggression?

The answer to this question is closely connected to my 82-year-old mother, who was born in Kostroma. She's been living in Kharkiv since we came here from Kazakhstan, almost forty-two years ago. Between February 24 and early May, I tried to persuade her to evacuate the city on several occasions, but she (and her beloved cat Murka) refused to leave. "We don't go anywhere. This is our home," she firmly told me. So, I call her several times weekly to check in on her. During our conversations, I inform her about the situation in Ukraine and around Kharkiv. All my telephone conversations with my mother are saved and numbered for posterity. She knows that my longtime friend Oleh Supereka is in charge of one of the Kraken units of the Ukrainian Armed Forces defending the city, and she always asks me about him. As I speak these words, he is recovering in the hospital after surviving a direct missile hit in Kharkiv on June 26.

One of our apartment bedrooms had been already destroyed, and the window was boarded up after five missiles hit the residential area on March 17, killing one woman nearby. My mother was knocked down by an explosion shockwave while heading down the staircase. At 1:00 a.m on June 18, our building got hit for the second time. On June 22 – what a symbolic date – my mother said to me, "They bombed the city twelve times today, two in the morning and the rest later in the afternoon." She described how she stood barefoot in a corridor per 'the rule of two walls' that every Ukrainian knows and added, "I was so scared. For how long are they going to keep doing this to us?"

Conversation number 50 started with my usual question about how her day was. She told me that her day was relatively calm, everything went as expected, and she read between her daily chores. Then, at one point, she said, "I want to tell you something. All the women here, both old and young, use just one word to describe Russia – murderers. And I agree with them." On June 27, she saw several jets flying overhead and not far from our building, "so loudly and so low that it seemed they were touching the tops of the trees." She paused for a moment and then said very articulately, "Those planes were ours, the Ukrainian ones. People saw the yellow-blue circles."

The city of Kvitka-Osnoviyanenko, the Budynok Slovo and Mykola Khvylovy, the Berezyl' Drama Theater, and Les Kurbas...my Kharkiv represented an interesting issue itself, even after 2014. The former mayor, Kernes, a guy who served his time in prison for fraud when I studied at V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, was a well-known pro-Russia character who described Putin as 'a good manager'. People in the city were divided. You could take a taxi and hear the driver say 'things are not so simple' or 'it is all because of these f… politicians', etc. and some would keep spreading the Russian propaganda about a so-called 'civil war' in the occupied parts of Luhans'k and Donets'k regions.

Now that's all gone. Those in Kharkiv who either had personal reservations regarding Russia's potential for evil or were rabid supporters influenced by propaganda have become entirely sober. 'Eyes wide shut' no longer pertains to them. And it could be no other way, given Russia's sadistic and depraved indifference to human life. Kharkiv is Ukraine, and it is an established fact, as straight and clear as it has always been for people like me, my friends, and my parents. And when on June 24, my alma mater closed the Russian language and literature department for good, forming the Slavic Philology department in its place, that decision seemed not just a symbolic act but an absolutely logical and historical statement.

President Zelensky awarded not only Kharkiv but Chernihiv, Mariupol, Kherson, Hostomel, and Volnovakha the title of “Hero City.” During a panel I participated in at the Harriman Institute shortly following the start of the invasion, the film scholar Yuri Shevchuk declared that we must find new terms to describe Ukrainian acts of heroism since this title was used back in Soviet times. What do you think?

The Soviet title ‘Hero City’ has been a controversial issue since its origin. It was introduced in 1965, but the four cities, Leningrad, Odesa, Sebastopol, and Stalingrad, were called ‘Hero Cities’ back in May 1945. According to historical documents, the highest title of Hero is given to the city for numerous acts of heroism and bravery of its citizens. By 1985, the number of decorated cities increased to 13. However, Kharkiv was not on that list. They say that the Soviet apparatchiks didn’t award Kharkiv this title because of the number of casualties – in all three battles for Kharkiv during WWII, the Nazis and Stalin’s Red Army lost more people than in any of the other battles fought for any city in Europe, including Stalingrad. Kharkiv was also the most destroyed city in Europe after Dresden. The fighting for it lasted longer than the battles for Kyiv and Odesa, and it suffered two occupations. So, the hypocrisy of the Soviet regime in ignoring Kharkiv is more than evident.

Ukraine has been defending itself in a war against the most deranged enemy Europe has seen since the end of the Second World War. Putin’s Russia is a country as sadistic as Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union put together, the two equally inhumane regimes as Vasily Grossman described them in Life and Fate. The discourse surrounding titles makes sense, and we clearly understand that every Ukrainian city, town, and village is heroic. Every Ukrainian citizen is a hero. Ukraine is setting a daily example for the world with its unheard and unparalleled bravery and self-determination in this fight against absolute evil. So, finding the term to commemorate such stoicism – and this term will be undoubtedly found – for the next generations of Ukrainians to keep in their hearts is just a matter of time.

In a previous conversation, you told me that Ukrainians like the activist and YouTuber Serhiy Sternenko represented the kind of people you had always hoped would exist in Ukraine. Could you elaborate on that? What appeals to you the most about the spirit of Ukraine’s younger generation?

Serhiy Sternenko and many other equally important individuals in Ukrainian society like Yanina Sokolova and Andriy Luhansky or the guys from Telebachennya Toronto represent the perfect example of what could be called Ukraine’s backbone. They grew up without the brain-damaging influence of Soviet ideology. By contrast, I was an ordinary kid in the Soviet era who began to discover Ukraine’s history and culture independently by listening to Radio Free Europe, BBC or Voice of America. I found that many things were quite different from all the songs and folk dance representations of Ukraine promoted in the Soviet times. At that same time, you couldn’t ask questions openly. I had to be careful if I wanted to obtain more information about Vasyl Stus or Lina Kostenko, for example, or about such dramatic pages of Ukraine’s history as the Holodomor, after discovering that my own family were victims of it.

The young generation of Ukrainians of the ’90s and the aughts know the history of Ukraine, both political and cultural, naturally. They speak, write, and express their ideas freely. Their active social life is devoid of self-censorship – they don’t even know what censorship is and what it’s like when you are not expected to say things openly. They all act independently regarding social awareness issues and personal involvement on all levels.

So, the difference is astounding when you compare today’s younger generation of Ukrainians with their peers from Russia. For the past thirty-two years, Russians’ lives have been deeply rooted in a past contaminated by post-Soviet imperialistic ressentiment, this Kafkian and Bosch-like alloy composed of chauvinism, Orthodox Christianity (with their archbishop who is a former KGB agent), and historical revanchism. Ukrainians, meanwhile, are living freely and looking to the future, while Russians still walk the streets and squares named after Lenin in a country where the Communist Party still hasn’t been banned, where the Czarist symbols go together with the Bolshevik hammer and sickle just fine. No wonder they came to their logical finale – the half-swastika ‘Z.’

…And the pain – that pain you feel when you see that the brightest young Ukrainians of today’s generation are dying for the country in this war of humanism against totalitarianism – Serafim Sabaranskiy in Kharkiv, Roman Ratushyi in Izyum, Semen Oblomei in Severodonets’k and many others... It is just unbearable. It’s pain on the level of some other cosmic dimension.

Although you are of Ukrainian and Russian heritage, you’ve always said that you’re fully Ukrainian in your heart. So, what does it mean to be Ukrainian?

Everyone’s answer to such questions is very personal. I spent almost nine years in Russia, but I grew up in Ukraine, where I finished school and graduated from my first university. When I worked in Moscow, I remember how many people kept asking me, “Why don’t you get a Russian passport? It will solve all your problems, and many things will become easier for you than they are now because of your Ukrainian passport. You always have issues with apartments and registration, police stop you in the streets, and when you get all those visas in European consulates, they start asking stupid questions once they see you are Ukrainian.” My answer was simple – no. Why is that? I guess it is just because since 1980, when I first heard “Chervona Kalyna” sung by my father, I’ve never been able to keep my eyes dry when I hear this song, each and every time.

Conversely, I’ve been taken aback by numerous Russian liberals who, since February 24, have felt the need to declare that they have Ukrainian roots yet know nothing about, say, Ukrainian dissidents such as Vasyl Stus who are so important to Ukrainian identity, especially now. What’s more, these Russians who poorly try to masquerade as Ukrainian allies continue to spread ideas that are harmful to Ukrainian statehood. Is there any hope for such people, or are we better off without them?

I stopped analyzing these differences many years ago when I heard Brodsky’s poem “On the Independence of Ukraine” which he wrote in 1991. This poet is considered an etalon of Russian poetry of the second half of the twentieth century. His poem is so full of chauvinist bile that I believe his favorite poet John Donne would be spinning in his grave if he heard it. Brodsky’s choice of words serves the only purpose – to express his beliefs of Russian superiority. The lines are disgusting, as he spews out specifically arranged folksy words the Soviets consistently applied to Ukrainians. In the final two lines of this poem, Brodsky intentionally uses a derogatory and utterly despicable rhyming of the word ‘mattress’ with the name ‘Taras.’

Knowing Vynnychenko’s famous saying on where the Russian liberal ends, it’s tough to disagree that Ukrainians are better off without such Russians. And you can’t help quoting Les’ Poderv’yans’kyi, “The national idea of Ukraine is – just f… off, leave us alone!” Ukrainian people had 31 years of re-established independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and they built a nation. The people of Russia had the same number of years in their favor, yet they have failed cataclysmically as a nation.

This war made everything very clear and set all the records straight. Everything is black and white—there are no shades of grey. Suppose those Russian ex-pats and individuals of all sorts who fled Russia, both journalists and writers, etc., dare to openly admit to themselves that they really did fail, that they were no help to their own country. Can they be of any use to Ukraine, a country possessing an intellectual powerhouse of contemporary writers and singers, let alone historians, movie directors, and journalists, that any other country would envy? Andrukhovch, Khlyvnyuk, Lyubka, Maljartschuk, Sentsov, Vakarchuk, Vengryniuk, Yakimchuk, Zabuzhko, Zhadan, to name a few... Does Ukraine really need to endure Russians who want to explain why things went so horribly wrong for them? Do Ukrainians really wish to dissect the semantics as to why it happened that those Russian criminal leaders went utterly insane and declared Ukraine should not exist, killing as many Ukrainians as possible? Are you kidding? We don’t need them. Anyone who suggests otherwise has no moral validity whatsoever.

You’ve now resided in the United States longer than anywhere else. As an American, I never felt at home there and was desperate to leave because the culture–or rather, lack thereof–was suffocating. Yet despite this inherent strain of anti-intellectualism in American thought, many Americans have shown an unprecedented outpouring of support for a country that, before February 24 most knew little to nothing about. What has it been like for you to witness this? Do you ever dream of returning to Ukraine since it has now proven itself to be the new central point of the free world?

Americans aren’t exactly known for being aware of what’s going on in other countries. The fateful events of 2014 came into their lives for a short time. Yet by 2015, the American public's interest in Ukraine had begun to recede, and eventually, the news stopped reporting on it all together. I don’t even remember anyone asking me about what was going on in Ukraine by the end of 2019. Americans moved back to their regular zones of comfort like the Kardashians, American Football, and U.S. domestic issues for the more socially inclined.

After February 24, their reaction to the war was different. It was avalanche-like in its development, growing bigger and bigger each day. Indeed, it is the first time that an invasion of such scale has occurred in Europe since the Second World War. My New York City district congressman contacted me. I can only imagine how many Ukrainian Americans and other U.S. citizens were pouring into Washington D.C. from all corners of the country, calling their politicians to action and urging them to launch the new Lend-Lease Act to help accelerate military aid to Ukraine. Many Americans who know me began to ask about ways to support Ukraine, and some of them became sponsors of Ukrainian families. The circulation of images and news about Kyiv was constant. And when the U.S. learned about Bucha, Irpin, and Borodyanka, it shocked everyone. Mariupol and Kharkiv became symbols of fierce resistance.

And as for my ever dreaming of returning to Ukraine…

Sometimes, it looks like Ukraine has never left me, and I’ve never left Ukraine. My younger cousin on the Ukrainian side of the family, a father of three sons, once said I would never find my place of home and peace. Ukraine is like a magnet for me or, to be more precise, we are like two magnets connected by a string; both of us have our own minus and plus sides. We are constantly rotating, changing. And you don’t know what is more likely to happen, that is, if we will ever finally cling to each other for good, or if we’ll just keep on rotating, again and again.

Interviewed by Kate Tsurkan

Cover photo of Dmytro Kyyan by Alexandra Muravyeva