“Every Ukrainian must do their part”: An Interview with Taras Polataiko

Taras Polataiko is a Ukrainian-Canadian artist from Chernivtsi. He lived and worked in Canada for three decades years before returning to Ukraine following the 2014 Maidan Revolution. His work, which often explores political history and memory, has been exhibited in galleries and museums across Ukraine, Germany, Poland, Israel, South Korea, the United States, Canada, Brazil, and various other countries. Polataiko spoke with Kate Tsurkan about his love-hate relationship with Chernivtsi, its many conflicting layers of history, how the artist became a wartime volunteer for the Ukrainian Army with his collaborative art project Someone Prays For You, and more.

You spent most of your adult life in Canada working as an artist and teaching at university. What differences (if any) did you observe regarding how the Ukrainian diaspora engages with its cultural legacy compared to Ukrainians themselves?

I think the evolution of the Ukrainian diaspora– especially in Canada–has been marked by the absence of a mainland cultural center. For over one hundred years, the Ukrainian diaspora was centered around the idea that it was responsible for preserving Ukrainian culture while it was systematically erased by Russians back in Ukraine.

There were several waves of Ukrainian immigration to Canada. The first one started at the end of the nineteenth century when Ukrainians (mainly from the west of Ukraine, which was then part of the Austrian Empire) moved for a better life in the New World on invitation from the Canadian government to settle and cultivate the Prairies. Many of them were poor farmers who sold their land and spent all their money buying a ticket to cross the Atlantic and get to Halifax. From there, they took a train to Winnipeg. Once they got to their promised piece of land, they had to dig into the ground and live like that before they earned enough money to even build a house. This is how a lot of communities on the Canadian Prairies started. Along with houses, they would build a church, open a general store, publish their own newspaper, and so on.

The second wave of Ukrainian immigrants came to Canada after the Second World War... These were primarily people displaced by the war who wanted to escape the threat of Soviet political oppression. In contrast to the first wave, they were educated professionals who settled in large Canadian cities like Toronto and Montreal and quickly established various community organizations. The third wave came after the collapse of the Soviet Union, including people from just about every walk of life who wanted to run as far as possible from its aftermath. Today, we’re witnessing the fourth wave of Ukrainian immigration to Canada–those fleeing Russia’s terroristic campaign.

The Ukrainian diaspora–not only in Canada but, dare I say, worldwide–is pretty conservative regarding culture. This makes sense, given that their goal is preserving Ukrainian culture and traditions in the absence of a mainland cultural center. On the other hand, there are leading professionals of Ukrainian origin in every field of human activity, including contemporary Canadian culture, science, politics, business, and so on. Ukrainian immigrants have fully integrated into Canadian society and contributed to it without losing sight of their roots.

What brought you back to Chernivtsi? Did you experience any culture shock coming back, even though you were born here? Due to the pandemic and now the Russian invasion of Ukraine, I haven’t been and likely won’t be back to the United States for a long time and always fear that it will be very difficult for me to re-engage in the way of life there, even if only for a short visit.

I returned to Ukraine in spring 2014 after the Revolution of Dignity. I was teaching art in Canada when the Revolution began in Kyiv. It was an extraordinary nerve-wracking half a year. I was glued to several news feeds nightly (because of the ten-hour time lag) and showed up to teach at the university the following day red-eyed and exhausted. Watching people get beaten and shot dead at night and having to switch to teaching issues of contemporary art, pretending you're normal, like everyone else, was pretty weird. My sense of reality was fractured. The worst was the sense of guilt for not being there, of being nothing more than a voyeur. So I got in touch with Ukrainian photographers who were shooting the protests and curated a traveling fundraiser show to help. I taught until the end of the term and immediately flew to Kyiv.

I had a show scheduled at the National Art Museum of Ukraine but I couldn't focus. I had come up with the idea for that show before the start of the Revolution. It was about the subtleties of intercontextual plays with art objects from Ukrainian museum collections and objects from real life. Thinking about it when the Russian invasion had just begun didn’t feel right. I remember our museum group going for smokes outside and talking about guys who went east to fight with no ammunition and the possibility of Russian tanks invading Kyiv from the north. So I told the museum I wanted to postpone the show and suggested doing a fundraiser instead.

It had to be something quick and efficient. I asked photographer Pavlo Terekhov to come with me to the Kyiv Military Hospital to shoot a series of portraits of wounded soldiers. I also recorded interviews with them about their experiences at war. This became a fundraiser for injured soldiers called War: 11 Portraits which launched a long-term Museum fundraising program to help the wounded. The show first started traveling to Ukrainian museums and later internationally in New York, Toronto, Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton, and Warsaw. The Canadian Embassy in Warsaw didn't have large enough space to fit it, so we hung the portraits on the fence of the Embassy.

I decided to stay in Ukraine because, after the Revolution, I had a strong sense that what was happening in Ukraine would change the world. To say the least, it's never boring here. I never imagined that I'd come back to Chernivtsi before that. There was an uncanny moment a year prior to 2014 when I went to India. The heat was 48 degrees celsius during the day and 37+ at night. I was on antimalarial drugs and couldn't even drink beer (it burns your liver if you do). I cut my trip short, flew to Ukraine, stopped taking Lariam, got drunk, dropped on my knees, and kissed the earth, thanking the green grass and cool breeze running through it. This was the first time since leaving Ukraine in 1989 that I thought this was a great place to live. Unfortunately, it took a revolution to make that happen.

Chernivtsi was once a gem of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and despite the horrors of history it bore witness to, this region has birthed some of the most important artists of the past few centuries. How would you describe the Chernivtsi of today? I often hear from people how fond they are of our quiet city, but do you think they truly appreciate its cultural legacy?

I have a love–hate relationship with Chernivtsi but I’m still here, so I guess I love it more than I hate it. I hate the ill-informed, pompously provincial and self-congratulating attitude that’s so prevalent amongst a certain part of the population. At the same time I love the quiet charm of this city because every stone speaks to me of my childhood memories. You never really understand what’s special about your childhood home until after you’ve already left it. In that sense, I’m glad I returned.. Only then you realize that this place triggers a pure and robust imagination in you that you thought was lost to age.

The history of Chernivtsi is a whole different aspect of its own. My sense is that Chernivtsi is built on memory gaps. There's the medieval part, the Austrian part, the Romanian part, the Soviet part and the Ukrainian part. All of them are disjointed because at each period the memory of the previous one was erased. The city as we know it was built starting in 1774 when it became Austrian. The Austrian period was the most inclusive, tolerant and multicultural. When the Habsburg Empire fell apart in 1918, the Romanian authorities got busy erasing markers of that culture and developed plans for ethnic cleansings of the non-Romanian population. That ethno-nationalism culminated in the Holocaust and the deportation of thousands of Czernowitz Jews who had happily lived here for many generations and contributed a lot to the city’s cultural identity.

When the Russians came in the 1940’s, thousands of people in Chernivtsi were deported to Siberia. Everyone who was able to flee did so–usually to the west. This multicultural European city became empty and got re-populated by badly dressed, gloomy, aggressive Russian-speakers who already lived under Stalin’s terror for two generations. They brought that “culture” here. Paradoxically, the representatives of that “russo-proletarian” culture happily moved into nice European apartments, private villas and quickly imagined themselves as a new aristocracy who looked down at the few surviving native Czernowitzers as hostile representatives of an alien civilization.

I grew up in the late Soviet period of 1970-80’s when Chernivtsi was a gray, gloomy, and predominantly Russian-speaking city. Its richly decorated and crumbling facades, along with the stories passed through generations, produced a strong sense of disjointness and got me interested in the city’s lost history. It was a sense of being born within European architecture and slowly realizing the weirdness of Russian slurs inside Habsburg buildings. I think I was one of the lucky few to have such realizations early in my life. Most people accepted this reality without questioning it.

Since real history wasn’t taught in schools, I had to hunt for old books. Sneaking into the “makulatura” room (school children were told to collect old books for reprocessing) at school and digging through piles of books was one of my favorite things to do. I was also addicted to nightly western shortwave radio broadcasts which were jammed, so you had to keep turning the knob to get a better signal. At some point I found out that Romanian TV showed American cartoons. I kept bugging my dad to install a hand made antennae on our roof. He made it out of an aluminum fold-out bed so I could watch “Tom and Jerry”, interrupted by hissing jamming noises and dead screen. Western music came from smuggled in vinyls and was re-recorded on reel-to-reel magnetophones.

Only the most popular stuff was available, though. So I figured that I could try to record music from shortwave radio. That was a whole process of its own. You had to find a relatively unjammed station, wait for the music, and quickly switch your reel-to-reel into record mode. If you were lucky to get the song you wanted, you had to rewind and re-record it to another reel-to-reel and erase the rest from the first bobbin to save space. I still have those old reel-to-reel bobbins with chunks of the songs somewhere at my parents’ house.

My first acquaintance with Western philosophy banned by the Soviets happened when I was a teenager. My dad’s fellow artist Petro Hrytsyk had early twentieth century editions of Nietzche and Schopenhauer. He kept them in a secret space between the walls of his apartment which he used as a photo lab. It took a long time before he agreed to lend the books to me for a few days. I really wanted to have a copy of my own. So my mom, who taught at school, made a deal with a technician who ran a huge copying machine called “Era” to make me a copy of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. I still have it.

Staying on the topic of Chernivtsi history and its influence over our collective psyche, could you expand on what you’re referred to as “the Austro-Greek School of Psycho-Analysis”?

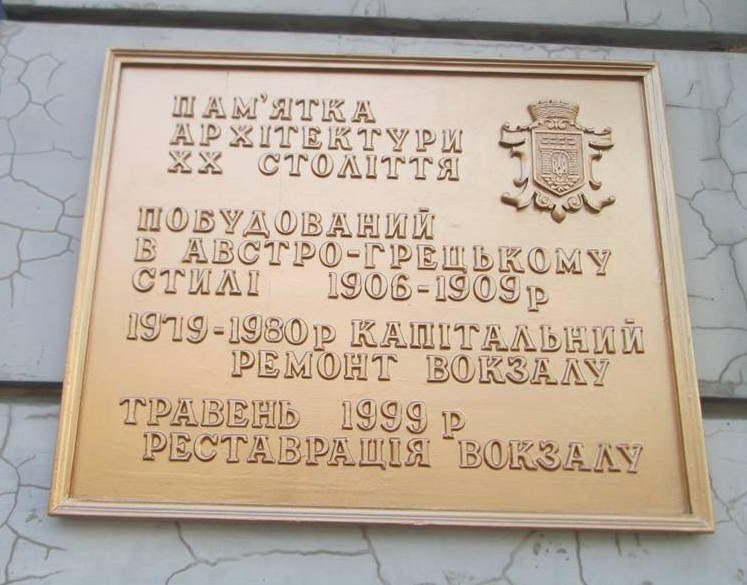

The Austro-Greek School of Psychoanalysis is a psychoanalytical branch of the Austro-Greek Empire. At some point in my new life in Chernivtsi, I discovered a newly-installed, gold-painted memorial plaque on our central railway station. The plaque stated that the building was built in the Austro-Greek style. I took a shot, posted it on Facebook, and received a message from the Chernivtsi Department of Preservation of Cultural Heritage asking me to remove it. Within a few days, the plaque was removed. A few weeks later, the director of the railway station was charged with taking bribes from employees of the railway station buffet. This piqued my interest and launched my research into the mysteries of the Austro-Greek style as a cultural phenomenon.

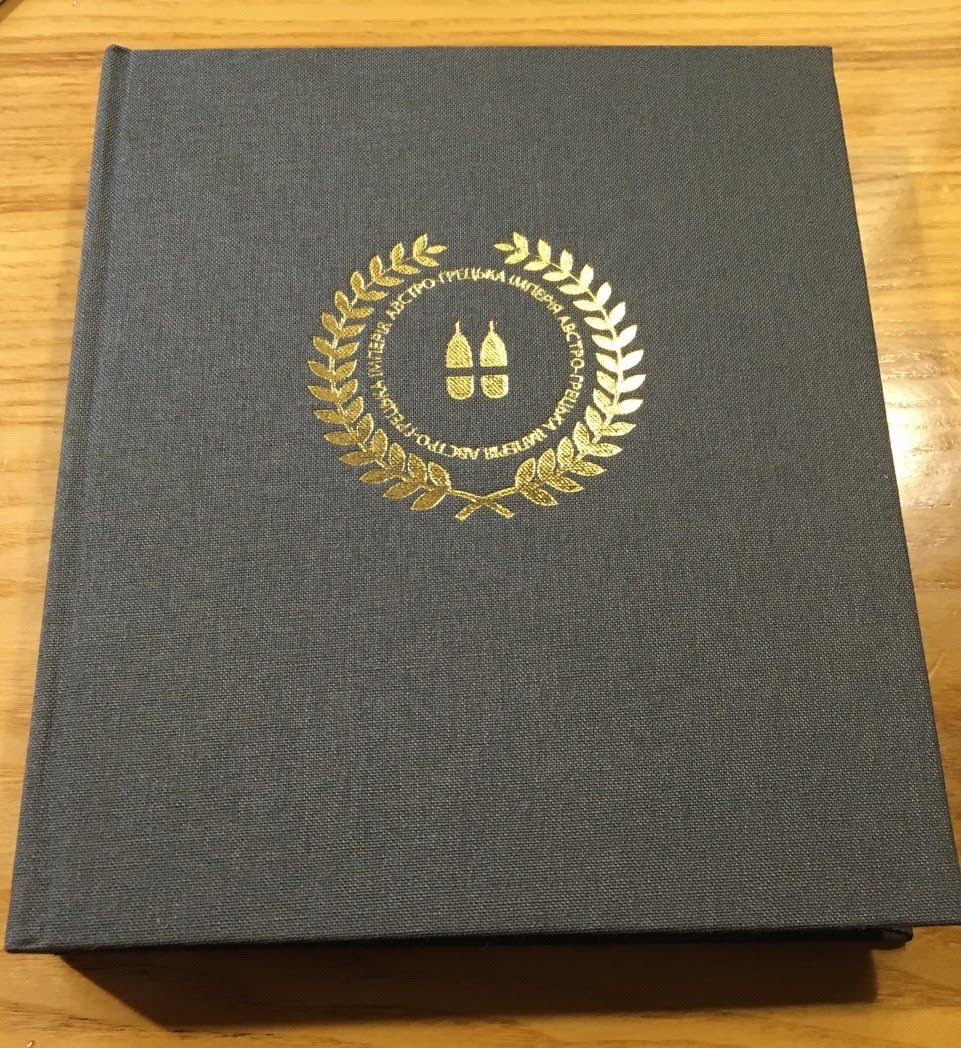

Now Austro-Greece is an empire with the capital in Chernivtsi that is rapidly expanding. It has its own genealogy, history, several colonies, herald, flag, school of psychoanalysis, a loyalty program with deep discounts for Austro-Greek citizens provided by the business community of Austo-Greece, and “passports” issued to new citizens. The book Spirit and History of Austro-Greece was published last year. It traces the origins of the Austro-Greek spirit all the way back to the first historically recorded forgery of the sacred stone with God’s will in Ancient Egypt that changed the course of history.

You've started a collaborative art project called “Someone Prays For You” which fundraises for the Ukrainian war effort. I have to confess that it brought a much-needed smile to my face, because it is one of those examples where we can say that art saves lives. So what is the life of a wartime volunteer in Chernivtsi like? Especially since we have–knock on wood–remained relatively untouched by the war, yet in your role, it occupies much of your waking day.

Me and my girlfriend Violetta were in Vienna when Russia's full-scale invasion started. All flights to Ukraine were canceled. Our tickets were to a Romanian city near the Ukrainian border, so we were able to get back to Ukraine that morning. When we got to the border, there was an incredibly long line of cars trying to flee Ukraine. We were the only ones trying to get back.

That morning was pretty weird and intense in many ways. My brother called from LA at five AM to tell me that Russians were bombing Ukrainian cities. At first, I was in shock, but I understood that I had to act quickly... Once we decided that we were heading back to Ukraine, we had to do all the usual things you do when you check out of an Airbnb. Finishing sorting the garbage into five eco categories while imagining your hometown under bombardment felt absurd. But you just have to tell yourself that you shouldn't let the horror of war stop you from being civilized, and you keep going.

The hardest thing was to see carefree people having their usual morning coffee on the streets of Vienna on our way to the airport. We realized that we were alone in it and that a lot of people simply didn't care. That hurt. Strangely, when we crossed into Ukrainian territory, where bombs could fall on our heads at any moment, we started to feel much better. We were home, and we were in the same boat as everybody else.

Violetta's brothers and their dad volunteered for the defense of Ukraine on the first day of war. They had battle experience from the 2014-15 war but no ammunition. They needed the most basic things like helmets, protective jackets, tactical boots, and so on. So we started buying everything for them. Tactical gear is expensive, so we quickly started running out of money. I had an idea to try fundraising by selling my photographs of artworks by local elderly artists, with 50% going to the artist and 50% to buy meds and gear for volunteer civilian defenders.

At some point, I got approached by my friend, the Canadian artist Janet Cardiff. Janet kindly offered her collages which she was making as her reaction to war news, for our fundraiser with 100% going for meds and gear. This broadened the framework of our fundraiser to international artists. Since then, we've been joined by Ukrainian artist Stanislav Turina, Austrian artist Angela Andorrer, Canadian artist David Blatherwick and Ukrainian artist Violetta Oliinyk. We're now able to help 60+ guys who're fighting in three different battalions alongside Violetta's brothers and their dad.

Eventually, the shock and fear that dominated the invasion's first few weeks wore off. Now our lives are more mundane. We get up, check for the latest updates, read messages from the guys on the front lines, and so on. Logistics of fund raising take up most of the time. At the beginning of the war, you couldn't buy any tactical gear in Ukraine. Everything was quickly sold out, and supply routes were disrupted. We drove to the big department store in Chernivtsi, hoping to buy everything we needed, but all we got was one leftover pair of tactical socks. It was pretty scary, to be honest. Even bread was scarce in the grocery stores for a couple of days.

So we started ordering items online from Poland and finding ways to get everything across the border. The postal service wasn't working. Slowly we developed our own logistical system: our guys call or message us from the front lines and tell us precisely what they need. Then we order everything online and deliver it to Violetta's mom's address in Poland. From there, it gets shipped to Chernivtsi either by bus or drivers take it by car. It changes all the time because the situation is fluid. One time we couldn't find any way to deliver stuff from Poland, so Violetta got on the bus and went herself. While she was on the bus, one border crossing was bombed, creating bottlenecks at other border crossings. She had to either wait on the bus for at least 24 hours or get off and cross the border on foot. The pedestrian line of refugee women with kids took eight hours, and sirens went off. In another six hours, she was in Krakow. She hoped to return the same day but had to stay for 2 days because her return bus was canceled.

Actually, come to think of it, most of the stuff wasn’t even available in Poland during the first few weeks of the war. People like us quickly bought it up. So we had to look further west. We got our first thermal drone from France, and thermal optics came from the UK and Bulgaria. At one point, there were no thermal drones available anywhere in the European Union, so we got one from Alaska. We now have a network of people like us who help each other out.

Shipping items to the front lines was a challenge during those early days of the invasion when the postal service wasn’t working. It had to be arranged online with private drivers. Everyone was in survival mode, going on very little sleep, adrenaline, and trust. I remember giving a $12,000 drone to the driver who was supposed to drive it to the east of the country. He didn’t want to take money from us when we told him it was for the guys on the front lines. I told him how expensive it was so he knew to take good care of it. When he drove off, Violetta told me I shouldn’t have told him because we didn’t know him. It got me worried. But the guy kept calling us from each roadblock to report his progress. He was great; later, he helped us deliver many other items.

Recently you caused a stir in Chernivtsi when you put up an art installation consisting of household items–such as a washing machine, vacuum, etc.–drenched in red paint in front of the city center monument to the fallen Red Army soldier. Why do you think this monument remains when city officials responded to calls to remove the red army tank monument shortly after the invasion began?

The official response from City Hall officials is that they need a permit from the Ministry of Culture to relocate the monument because it is on their list of sites of “cultural significance.” When I started a petition to use the Soviet tank monument on Gagarin Street as a site for art projects a few years back, I was told that it couldn’t be done there because it was also on that list. Yet they removed the tank shortly after the start of the invasion. Why is the monument to the red army soldier still standing?

People in Chernivtsi started bringing their own items to add to your installation, until one day, it suddenly disappeared. Did you get any response from city officials as to why or how this happened?

The City Hall removed my installation without any notice or explanation. They tried to hush it up as much as possible. At the end of the second day, a group of armed police with a dog approached people who wanted to take a photo, telling them that photographing it was forbidden to do so by "the highest authority."

People called the City Hall to find out why the installation had been removed. In the beginning, officials said it was removed because someone had dumped a pile of garbage on it at night, but photos published online showed that wasn't true. So then they changed their story and said that people had brought too many used appliances, thus creating an "undesirable pile of garbage at the city center." This obsession with cleanliness is bizarre, given that city officials are responsible for the chronically overfilled garbage containers all over the city.

I had invited people to contribute to my installation by bringing household appliances the Russians are looting from Ukrainian households. It was a way for people to express their feelings about the war crimes committed by Russians in Ukraine. People are traumatized by war. There's a lot of sadness and suppressed anger about Russian war crimes and horrible genocidal acts, as well as deep frustration about the likelihood of Russian war crimes going unpunished even after the war. Making it possible for people to contribute to the installation was a peaceful way of channeling that sorrow and frustration into art. Yet Chernivtsi city officials chose to grant themselves the moral authority to deny this possibility by deciding which objects are art and which are garbage.

Suppose you look at this Austro-Greek performance by the City Hall in the context of war. In that case, it looks like this: the country is covered by debris produced by Russian shelling of civilian infrastructure, and the city they're responsible for is covered with piles of garbage collected by corrupt, inadequate governance. Instead of cleaning garbage dumps, they're spending taxpayers' money on destroying an art object undermining the narratives of Russian propaganda.

This is what I hate about Chernivtsi and its shameless self-congratulating provincial nature. There's a Ukrainian saying, "To piss into one's eyes and say it's God's dew." It applies to local officials who behave like local tsars once elected. It also applies to the apathetic voters who elect them. It's hard to imagine such a brazen act in most other Ukrainian cities.

So the statement of this art installation was clearly that Russians obliterated whatever historical goodwill they had earned defending the world against nazis during the Second World War by becoming the great fascist threat of our time, killing, raping, and looting their way across Ukraine while declaring that they are prepared to do the same elsewhere. Not everyone has fully grasped the gravity of this situation yet, unfortunately. Going forward, how can Ukrainian artists and intellectuals lead the forefront of the information war against Russian colonial thinking?

Every Ukrainian must do their part to make Russian war crimes known to the world. The Russians are psychopathic sadists. Their "intellectuals" first dehumanize their victims through propaganda, then their army invades to loot, rape, torture, and kill civilians. The historical list of Russian war crimes and crimes against humanity is long. It includes the mass rape and killing of European women by the Red Army during the Second World War. After that, they invaded Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. They invaded Poland and Finland in 1939.

The collective memory of the West conveniently forgets about all their crimes because in all these cases, the Russians managed to end up the winners of history and got away without a proper war tribunal. This allowed Russian "intellectuals" to concoct the aggressive hate-based expansionist ideology of the so-called "Russian world." At the root of this revanchist Nazi-like ideology is revenge for the loss of the Cold War. Essentially it's an adaptation of the Nazi revanchism of the 1930s. If Nazi ideology was a projection of Hitler's hate onto the German population, the "Russian world" ideology is a projection of Putin's hate onto the people of Russia.

The victory over Nazi Germany is instrumentalized into a propaganda slogan, "Mozhem povtoritʹ!" which translates to "We can do it again!" It's directly opposite of the internationally accepted "Never again!" Once that slogan was set in the collective Russian psyche, it became much easier to convince the Russian population that countries like Ukraine needed to be “liberated.”

My art installation in memory of the victims of Russian war crimes took aim at this ideological construction. The irritation and controversy it caused is a testament to the extent to which the officials of Chernivtsi City Hall are subjected to the influence of Russian propaganda.

Ukrainians have no choice but to win this war. If we don't, we'll become the victims of a Bucha-like massacre on a nationwide scale. If we fail, they'll erase Ukrainian culture and identity like they've tried to do for centuries. If Ukraine falls, Putin will be in charge of the remains of a million-strong Ukrainian army. He'll use it to complete his mad vision of restoring Russian control to Berlin. He'll start with the occupation of Moldova. The Baltic states will be next, followed by Poland and the rest of Central Europe.

The expansionist "Russian world" model is based on the inability to create economic prosperity at home. It can be sustained only by an aggressive nationalist frenzy of expansion. Its ability to terrorize the world with nuclear threats is at the core of its brazenness. Russia must be denuclearized. The way to do it is to give Ukraine enough weapons to liberate occupied territories, restore international law and order and keep economic pressure on Russia till it faces economic collapse and agrees to denuclearize.

There will have to be an international war crime tribunal followed by a denazification program and reparation payments. This is the only way to ensure Russia will never be able to invade neighboring countries and terrorize the world again.

You can help support the Ukrainian Army by purchasing art from Taras Polataiko’s collaborative art project Someone Prays For You here.